On Political Advertising

14 October 2019

As I’ve said before this is not a political blog, and so what follows should not be seen through any partisan lens. That said, it’s time we thought a bit about the state of political advertising.

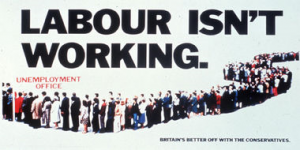

Back in the last century I worked in the agency handling the Conservative party account. The agency was Davidson Pearce, this was pre-Saatchi and the infamous 1978 Labour Isn’t Working poster that transformed political advertising.

Maurice and Charles Saatchi and the late Tim Bell modernised political marketing, not only through more aggressive advertising but also by coaching politicians in how to communicate effectively (Margaret Thatcher famously took lessons in lowering her voice to give the impression of gravitas).

Before Saatchi and Saatchi, political parties didn’t engage fully with ad agencies. We were a necessary evil that they put up with, because ‘the other side was doing it and so I suppose we should too’.

Party political broadcasts comprised a politician talking behind a desk – before someone worked out these things were basically free 5-minute commercials and should be treated as such.

It was accepted that all ads stopped a week or two before an election, presumably to allow the electorate to get over all the excitement before placing their vote.

The political ad scene was driven by gentlemanly behaviour, and was as boring as hell. How things have changed.

Political advertising is not subject to the same rules and self-regulation as ‘normal’ campaigns. For those unaware of the UK situation, ‘normal’ ads are subject to the rules laid out in our Code of Advertising Practice (CAP) and are regulated by the Advertising Standards Authority (ASA).

Both bodies are paid for by a levy on all campaigns and are thus free to the taxpayer.

The benefits of self-regulation are that it allows for flexibility, as habits and norms change, and for a speedy resolution of any disputes, quite aside from avoiding clogging up the courts and doing away with expensive legal costs.

But ads for political parties or groups (as opposed to Government ads which are regulated) are different. Here’s why, from the ASA:

“Political ads … usually inspire contention and debate. While we understand the calls for political ads to be subject to the same standards of truthfulness and decency that all UK advertisers have to abide by, there are a number of reasons why we don’t regulate them … Regulating traditional advertising is very different from regulating material that forms part of the democratic process. It would be inappropriate … for us to intervene in that process.”

But times change, and over the last few years, particularly since the calling of the Referendum on EU membership there have been ample examples of misleading ads that have led to the subject of regulation being raised.

These examples are not exclusive to one side of the Brexit debate over the other, but as passions have run high, ads and other communications have been put out that are either blatantly untrue or have been designed to mislead.

It might seem cynical to suggest that those responsible for these communications have taken advantage of the lack of regulation to lie with impunity – but that’s exactly what has happened.

Misleading political campaigns damage our industry by eroding consumer trust. After all, few outside the ad business know that these campaigns are not regulated.

It’s time this changed, not only to ensure that voters are made aware of the facts, as opposed to partisan lies, but also to ensure that ads are recognised as such by making it clear who’s paying for them.

This is essential, none more so than on social media where it is not even immediately obvious what’s an ad and what isn’t.

The non-partisan campaign group The Coalition for Reform in Political Advertising is arguing for change. It would be great if readers of this blog could support their efforts – their ambitions are good for all of us.

As an industry collaborator with the ASA and a member of CAP and then BCAP for many years, I recall a different spin to the ASA’s necessarily diplomatic statement you quote.

In short, many industry parties have long believed that political advertising should not be excluded from the industry’s world-leading self-regulatory system of ad content control.

They – in my view rightly – argue that its exclusion brings the system into disrepute, particularly as political advertising behaviours and transgressions have become more extreme.

However, despite the ASA relieving them very well of the headache of doing it themselves, governments and politicians of all stripes have long and most vigorously resisted inclusion. And they hold most of the cards :

– Their ad account is one of the largest and most sought-after

– Most industries rely on government for their licence to operate, advertising no exception especially at a time of threats to freedoms eg food & drink, and

– The ASA itself depends on continued government patronage for its delegated powers.

The ASA treads the delicate line between these two critical stakeholder groups with great skill, but it doesn’t alter the key issue, which is that politicians’ insistence on being beyond truthfulness and misleadingness regulation is corrosive to all parties, themselves included.